What camp are you in?

When it comes to making big purchases, there are two camps. Which are you a part of?

- Paying for it fully, upfront. These are your “cash in hand, I’ll get you the money tomorrow” kind of people.

- Financing, or paying in installments. If you don’t have a lot in your bank account, and you live paycheck to paycheck, this is probably you.

Personally, I’ve considered myself the first type. I like to pay for things immediately, and not have to worry about making payments three years from now.

But I heard an aside from someone

Pros and Cons (or so I used to think)

First, we need to start with the traditional benefits and drawbacks of these two approaches. We’ll start with paying upfront.

- Pros:

- The item is fully owned immediately, no-one can take it back.

- You don’t owe any money afterwards.

- Even if you’re in a worse financial position in the future, you don’t have any payments to worry about.

- You can immediately sell the item.

- No interest means you pay what it’s worth.

- Doesn’t hurt your credit score.

- Cons:

- You lose a significant sum of money immediately.

- It’s hard to come up with large amounts of cash.

- Could hurt your savings, especially if you don’t have an emergency fund.

- It’s risky to transfer large sums.

- Usually can’t use a credit card, losing out on potential rewards.

- You can’t run to another country to stop making payments.

In short, the biggest drawback is that people don’t have heaps of cash just lying around. But if you do, and you’re careful, seems like a decent idea.

Now let’s talk about financing.

- Pros:

- Financially small initial commitment – you can make big deals with not a lot of cash initially.

- Spreads the cost out, softening the hit.

- Allows you to pay more as your financial state improves.

- Lets you earn rewards on your credit card.

- Improves your credit score.4

- If there’s no interest,5 you’ll save a bit of money6 due to inflation.

- Cons:

- With interest, you end up paying more. Sometimes a lot more.

- If you get in a worse financial position, you might not be able to afford the payments.

- Falling behind on payments will kill your credit score.

- Long-term draw on your paycheck, leaving less money for other things.

- Lender can take away your asset, as they own it partially.

It is kind of nice to not have a massive sum of money just go *poof*, but who knows where you’ll be in two, three, five years from now?

So it’s a toss-up, right? If you’ve got heaps of cash, pay for it now. If not, pay later. What’s this whole article about?

The Big Pro

I haven’t been completely honest in my comparison.

Okay, okay. When you pay in installments, that leaves you with all your money still in your account, right? And it lets you earn credit card rewards. But the big thing that I missed is that you can invest the money you haven’t committed yet.

…That’s it? Obviously, if you didn’t spend the money, you can use it for other stuff. So what?

Let me put this another way: You can invest the money (that you will eventually use towards the asset) to earn a return that outpaces the interest costs. You can actually save money by paying in installments!

This idea came from Graham Stephan, a real estate investor and YouTuber, in his video How I Bought A Tesla For $78.

Huh. Like I said before, I had never thought of it that way. If, for example, interest rates are 3%, and you invested your money in an index fund that grew 5% every year, you’d make money instead of losing it.

Right?

Why the post isn’t done here

Interest is complicated.

If you’re paying a 5% APR on, say, $100,000, you’re not going to end up paying an additional five percent of the total, or $5,000. APR is the Annual Percentage Rate, and the math is very confusing, but according to a calculator I found online, if your loan has to be repaid in five years, you’ll end up paying $113,227.40, or an additional 13.22740% of the original cost.

So imagine you put that total in a savings account, and pulled your monthly payment from it. By the time the five years are up, would you have extra money? Or would the dwindling cash be unable to keep up with the interest?

It’s easy to say that “3% is smaller than 5%, so you’d make money”, but that is completely ignoring the complexity of compound interest.

We need to do some math, and I know you’re just as excited as I am.

Cars vs Real Estate

Before we get into it, I do need to address a quick

For example, if you bought a brand-new car for $100,000, after 5 years the value will drop by as much as 40%, which means your not-shiny-anymore car will be only worth $60,000, and you will have had a better ROI (Return On Investment) by keeping the money under your mattress.

In contrast, if you bought a small house for $100,000,

But anyways, we’re going to ignore all that. It’s too much math for one day, and I haven’t even gotten started yet.

The Fun Part

Before, I mentioned that an online calculator told me a $100,000 loan with a 5% APR would total $113,227.40 at the end of 5 years. But how does that math work?

If I simply took $100k and multiplied it by 5%, the total is $105k. “Simple Interest” is just that, multiplying the amount by a percentage, multiply that by the amount of years, and bam, you’ve got recurring income in your savings account.

But it’s not that simple.

That still doesn’t match the calculator, however, because unlike in a savings account, you’re not paying 5% on the full amount. You’re only paying 5% on what you haven’t paid off yet.

To simplify, let’s say you had a two year loan on the $100k, and you decided to pay $50k after the first year. After the first year, the interest adds 5%, or $5k, to the loan. Now you pay the $50k, but because of the interest, you’re left with $55k to pay off, instead of $50k. At the end of the second year, you get ready with $55k to pay it off, but the interest hasn’t gone away. Now the remainder has grown 5%, to $57,750. You grudgingly pay the extra $2,750, because what do you know, you’re just a simpleton in a big world of financiers and conglomerations.

If you add it all up, you have paid $107,750 on this loan of $100k, which is an additional 7.75%. See how interest is confusing? And I know that we have calculators to figure this all out for us, but if you can figure it out yourself, it helps to make it a little less like magic,

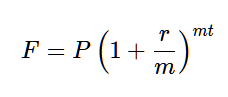

For those interested, the formula for compound interest is:

Where:

F = The Future Value

P = The Present Value

R = The APR changed to a decimal (e.g. 5% > 0.05)

M = Times the interest calculates, per year (e.g. 12 for once a month, 365 for every day)

T = The Number of Years

Sunset

Here’s a picture I took of a cool sunset, because all this math is making my head hurt and I need a break.

Ok, onwards!

Hold On One Second

Wait. I had an idea.

You know what people love more than really cool articles?

A series of really cool articles.

This one has been going on for too long, and engagement

So I’ll see you later, in part 2 of this thrillingly interesting article!

Go to part two of this incredibly captivating series by clicking “next post” on the bottom, or just use this link.

If you were the only person who clicked in the email sign-up “Long Posts” and nothing else, you’ll love this post on Objective vs Subjective Benefits.

But if you hated every second of it, yet somehow made it to the bottom, console yourself with The Motions of NYC.

Let me know in the comments below, on a scale of one to two, how much you loved this article.

Or just complain about how blurry the sunset photo was.

For real. As I write this, I have the idea in my head, but I haven’t done any in-depth research yet. You’ll get to watch my thought process in real time.

Which is obviously a clickbait title, but he makes good videos.

Also, percentages can be misleading. $75 is 25% less than $100, but $100 is 33% more than $75.

You can argue back that the value afforded by having a car, which lets you get to work, make money, etc., offsets the loss. Which, interestingly enough, is a similar calculation to what we’re talking about in this article.

Yes, I called this a post, and now I’m calling it an article. It’s getting quite long.

And yes, I know I can just edit it to be “article” or “post” in the entire article. But this gives more of a feel of how my mind works, and brings you along for the ride.

Apparently, you can’t put a footnote in a footnote

so now this will be a long line of footnotes. Hope you enjoyed the ride, please remain seated until all rambling has come to a complete stop.

I’m going to stick with $100k principal and 5% interest for all of these examples, unless stated otherwise.

The depressing kind, where the magician takes your dollar and makes it disappear.